A couple of years ago I gave a presentation titled "Collecting and archiving born-digital video" at the Society of California Archivists (SCA) 2017 annual conference in Pasadena. I'd always meant to post it online, but I wanted to write up text to accompany the slides. I've finally now done that.

For context, my talk was part of a session titled "Born digital: care, feeding, and intake processes." Other speakers represented the LOCKSS program at Stanford, the Internet Archive, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. A full description of the panel is available under session 10 in the SCA 2017 conference program.

A note about the text, which is true of pretty much every talk I've given since library school: I have a difficult time reading from notes when I do public speaking, so unless there's a long quotation I want to read exactly, I go without them. As a result, I don't have an official text for the talk, just the slides.

Since I'm essentially writing it up for the first time in 2019, it's not exactly what I said in 2017, not least because it's probably longer than fifteen minutes as written. But I've decided to go wtih the present tense anyway.

Hi, I'm Andrew Berger and I'm going to be talking about collecting and archiving in-house digital video, by which I mean video produced in digital formats. For background, I'm going to begin by telling a story, a story about a museum.

The Computer History Museum has had an active oral history program since the early 2000s. There are some oral histories from even earlier, mostly on audio tape, but the pace really picked up in the 2000s with the use of DV tape. Almost every oral history from that point on has been on video.

Around 2010-2011, there was a shift from using digital tape to using digital files, with all-file workflows taking over entirely around 2012-2013. Around the same time there was also a shift towards treating oral histories as productions, with an eye towards reuse in exhibits and documentaries. All oral histories are now shot in HD, many with special lighting, separate microphones, and a green screen.

Oral histories are seen as a collecting activity, with every production ultimately creating files that the museum is dedicated to preserving in the permanent collection.

Oral histories aren't the only kind of video the museum produces. Lectures and other events are routinely recorded, dating all the way back to the 1980s. These recordings span analog and digital formats, with DV tape taking over from Betacam and VHS in the early 2000s. Just like oral histories, these moved to all-file workflows starting around 2010-2011.

The museum has kept these videos as well, but is that the same as collecting them?

The museum also produces its own exhibit videos. These include not just the videos shown in the exhibits (on-site and online) but also the raw footage shot specifically to be used in exhibit videos. As with just about any video production process, it takes hours of raw footage to produce a few minutes of a final production.

Exhibit video production increased signficantly around 2009 in preparation for two major exhibits. As with oral history and event video, the museum retains its exhibit video.

Beyond oral histories, events, and exhibits, the museum produces even more kinds of video. There's footage of docent trainings, educational events, marketing campaigns--essentially, any public facing museum function could have a video component.

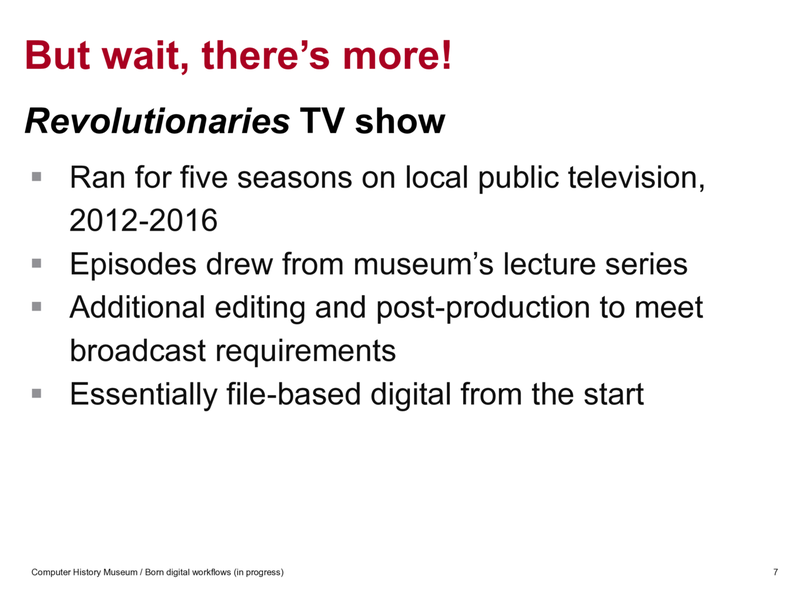

But wait, there's more! For five years the museum also produced a television show for the local PBS affiliate, KQED. This was an hour-long interview show that drew heavily from the museum's live lecture series.

The production of the tv show was essentially all-digital from the start. The lectures were recent enough to have been shot in HD, then additional editing and post-production work was done to transform them into files meeting broadcast standards.

The museum has retained copies of its television episodes as well.

To summarize, the museum has produced and is producing a lot of digital video, with a significant increase starting around 2009. This increase has coincided with a shift towards file-based rather than tape-based workflows.

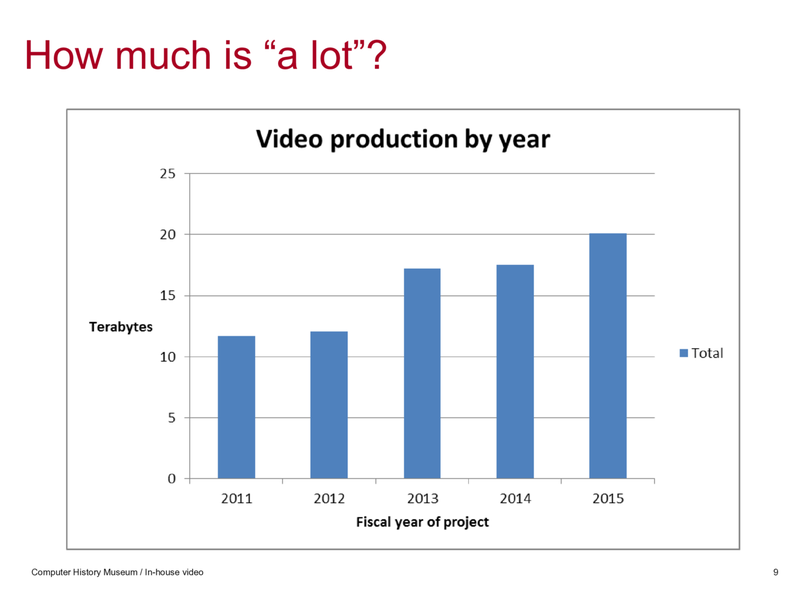

Now, you might be wondering, how much do I mean by "a lot"? This chart shows the approximate growth in video production from 2011 to 2015, measured in terabytes. The chart starts in 2011 because that's the first year for which I could generate reliable data, in part because for earlier years I would have to go back to tape. You can see there was nearly a doubling in production in four years, from just over 10 TB in 2011 to 20 TB in 2015. [Note from 2019: it's around 30 TB now.]

On a panel with representatives from LOCKSS, the Internet Archive, and JPL, twenty terabytes in a year might not sound like a lot. But keep in mind that for every byte of video, someone had to schedule the event, set-up the mikes and cameras, monitor the feeds, transfer the data, and edit the final products. This is artisanal, hand-crafted data.

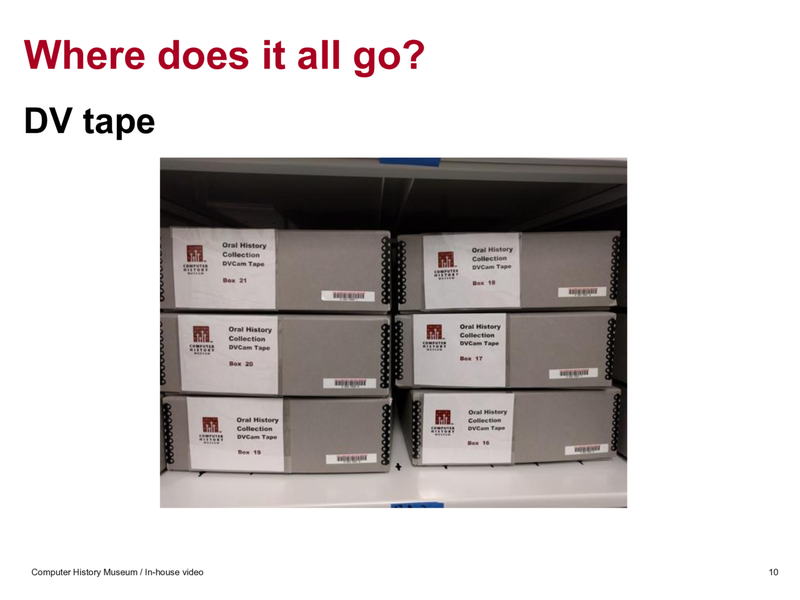

Where has all this data been going? First, as I've mentioned, it mostly went onto DV tape, which is stored in archival boxes.

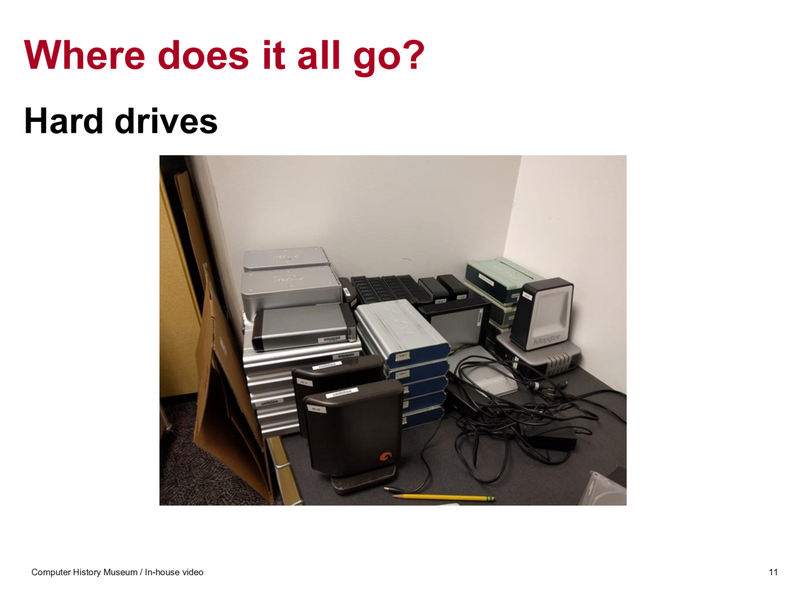

For a while, a lot of the data was also being stored on external hard drives. I don't even want to talk about the hard drives.

Finally, it started being stored on servers. These have grown quite a bit in size. Since about 2013, the media production team has had their own system combining server space with LTO tape to use for editing and backup. And in 2015, the museum launched a digital preservation repository. The vast majority of the data in the repository so far is video.

How has the museum adapted to the challenge of managing and preserving all this video? That's the subject of the rest of my talk.

First, file formats. I'm not actually going to spend a lot of time talking about formats, even though it sometimes feels like that's the main thing people want to talk about when I get asked about digital video preservation. I will say that there are multiple different production formats and codecs in the collection, some of which are proprietary.

In the absence of a generally agreed upon normalization target within the broader digital video community, we've settled for preserving the "original" digital formats as long as they can be opened with open-source tools, specifically VLC and/or ffmpeg. We might normalize or migrate to other formats in the future but at this point the costs and risks of normalization would outweigh the benefits. This decision does have the side effect of making the preservation of VLC and ffmpeg more important to our overall preservation efforts.

Note that this policy for digital sources is different than our policy for digitization from analog sources, in which case the file format is entirely up to choice.

Video files are intense: not only do they take up a lot of disk space, they also require more powerful processors for rendering and playback. The museum has had to upgrade its technical infrastructure to handle them. As I mentioned above, server space for editing and storage has been greatly expanded. So has internal network bandwidth and computing power for staff that work heavily with video.

But the biggest changes have been in terms of what I'd call the conceptual approach. What does it mean to say you collect or archive video? Oral histories, as I've mentioned, fit solidly into the collecting paradigm, even if they are produced in-house. They've always been on a workflow to be accessioned, cataloged, transcribed, shared.

What about the other video production types? What about their raw footage? What if there's only raw footage?

On this slide I've included two photos of boxes of digital video tape. One contains oral histories and has nicely printed labels. The other contains lectures, and though you can't see it on the slide, the boxes are labeled in pencil. I think this captures the tentative nature of how video was being preserved outside of oral history, as if it still wasn't ready for the permanence of labels.

One way to look at the problem is to step back and ask, what is video, really? Yes, videos are shot to create digital objects, but video is also made to document activities. Video production can be seen as an institutional function that produces institutional records as video.

As it happens, the museum doesn't really have an institutional archive separate from the general collection. Nonetheless, it's been helpful to approach video as records and to ask, if there were an institutional archive, and if it were arranged around functions and departments, then where would these video files fit into that arrangement? Can they be understood in terms of records scheduling and retention (but without actually using those terms in casual conversation)?

Given that it is not, in fact, possible to preserve everything, we've been working out appraisal and selection policies with the media production team and other interested parties, depending on the type of video project and how it fits within the context of the whole institution.

For example, a single lecture could produce upwards of 500 GB: three camera feeds, one live "switch" feed drawing from the three cameras, final edits for the online audience, and possibly even another version for broadcast television. For long-term preservation we save only the switch, the public audience version (i.e. the version posted to youtube), and the final broadcast file if there is one. The goal is to balance future re-use value with the goal of documenting the event, rather than saving every single file.

For other kinds of production, such as exhibit videos, we keep much more of the raw footage, sometimes even every camera feed. The media team also saves more data on their production system, but these are considered active records within the context of the whole system.

Another significant change we've made has been in terms of staffing. Previously, there was a position of Oral History Coordinator, which focused mostly on the oral history program, but had some duties related to video production. For various reasons, this position didn't manage or monitor video files after they were produced, and no archivist became involved until the end of the workflow. But the previous holders of this position kept getting promoted (a good thing!) to work more specifically on content production, which had the side effect of making us take a fresh look at the whole video production and archiving workflow.

In the new arrangement, there's an AV Archivist who works closely with one of the Media Producers as the main points of contact between teams. The AV Archivist keeps abreast of all productions that will potentially produce material to be preserved and, in combination with myself, tracks files from production to preservation and access.

There's also a regular check-in between the archivists and the media team where we keep up with current projects and review what's working and what could be improved.

The final significant change we made was to how we manage the actual moment of transfer of files between the production team and the archives. Previously, files were being dragged and dropped over the network, which is not the ideal way to move files that could be hundreds of gigabytes in size. When a copy was interrupted, there was often no way to tell that something had gone wrong until an archivist found a corrupt file.

Now the production system has been configured to generate checksums for each file, and to send files to the archives staging area with corresponding checksums included in an accompanying XML file. This way the archivists can validate the checksums as the files arrive and identify problems earlier in the process.

This is all still a work in progress, so I don't really have a grand conclusion. There's still a lot to do in terms of improving file management and settling on appraisal and selection decisions.

But I will say that as the museum has continued to increase video production in nearly all areas, it's difficult to see how the increase could have been managed without making these larger organizational changes. We may have started with preservation as the end of the workflow, but bringing preservation concerns upstream has helped us see the bigger picture. This has really paid off when requests have come in for previously produced footage and we've been able to say, without too much trouble, yes, we have that and we can get it again.